The Art of Rolleiflex

The Art of Rolleiflex

Many others have written about the technical reasons as to why the Rolleiflex twin lens reflex cameras were, and remain, such an enduring success (large negative size, superb lenses, etc.), so I’m not going to reiterate any of that here. Apart from all those reasons, and in my opinion, the Rolleflex cameras are some of the most beautifully designed cameras of all time, and are works of art in their own right.

This article, therefore, is just an excuse to post some photos of the three cameras I own; pure ‘camera porn’, if you will. In an age when camera design has morphed into the current black plastic blob aesthetic, I think it’s an apt reminder of a level of craftmanship that has sadly become a lost art.

Admittedly, I have a soft spot for twin lens cameras; my Dad used to shoot with a Yashica E and I remember as a young boy being completely fascinated with this camera. Apart from that, the negatives he made of our travels around the world have survived the test of time very well, and the quality that the 6×6 negative brings to the table is still readily apparent when viewing them even today.

One of the things I love most about these cameras is the view through the waist-level finder. If you are used to squinting through the tiny eye-level finder of a modern DSLR, the huge image you’ll see on the ground glass screen of a Rolleiflex is a revelation! Yes, the view is laterally reversed, which causes some initial disorientation if trying to track a subject, but being able to see the entire frame that will be captured on film is a fantastic way to compose a photograph.

The finder hood also incorporates a magnifier for critical focusing. When open, pulling upwards on a small catch on the inside of the hood causes the magnifier to pop up.

With the magnifier raised, pushing in on the front panel of the hood engages the third viewing option, the direct view. In this configuration you have a direct eye-level view of the scene though a small frame in the rear of the hood. This is useful for tracking subjects because it is not reversed as in the other viewing modes. Just below the direct view window, a clever system of a secondary magnifier and a small mirror gives you a reversed view of the central portion of the ground glass for focusing.

The direct view and the focusing view are close enough together to enable quick switching between both. Pushing down on the silver catch below the magnifier returns the hood to it’s original position. This is another reminder of the ingenious mechanical and optical design of the Rolleiflex.

For a medium format camera that produces 6×6 cm negatives, the Rolleiflex is fairly compact. With the hood folded down, and the film wind crank stowed, it makes a comfortable ‘brick’ that is easily carried. Also, because it has a fixed lens, there is no temptation to load up a bag full of extra lenses when you go out to shoot. A Rolleiflex, a light meter, maybe a filter or two, and a few rolls of film is all you need.

Not everyone can get on with the ergonomics of a twin lens reflex camera, and some just hate the waist level viewing, but I find the Rolleiflex great to use in that respect. With the camera on a strap at waist level (beer gut level, in my case), all the controls fall easily to hand.

Focusing is achieved with the large knob on the left (looking down) and the film is advanced with a fold-out crank on the right. Aperture and shutter speed are set using the two wheels between viewing and taking lenses, and the chosen settings are viewable in a small window above the viewing lens.

As shown in the ‘family portrait’ at the beginning of this post, I now have three Rolleiflex cameras. None of these are collector grade and they all show signs of fifty plus years of use, but they all perform beautifully.

1954 Rolleiflex Automat MX (Model K4A)

When I bought my Leica M3 last year, the retired photographer I got it from also sold me his MX which had been his main camera for portraits for over forty years. His career included working in a studio in New York where he photographed various famous and celebrity clients (he has negatives taken with this camera of Eleanor Roosevelt, amongst many others).

Although it’s a little cosmetically rough around the edges, it was obvious when I handled it that he had taken very good care of the camera; it is probably the smoothest and quietest of all three cameras, which validates his claim that, although he worked it hard, he also had it serviced regularly.

This particular example is fitted with the Zeiss-Opton Tessar 75mm F/3.5 taking lens. Variations for this model included the Zeiss Jena Tessar and the Schneider Xenar.

The MX has a much smaller focusing knob than later models so I added the Rollei extension knob to mine to make focusing a little more comfortable.

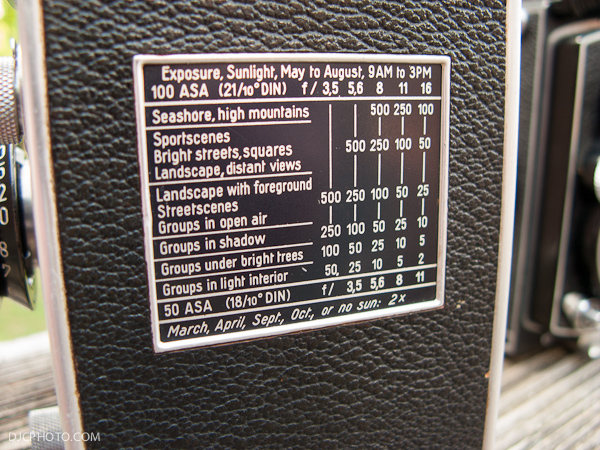

There is no built-in meter on the MX model, so a simple exposure chart is included on the back of the camera which gives approximate settings for various lighting conditions.

The red star on the taking lens denotes that the lens is coated to reduce flare and increase contrast.

1956 Rolleiflex Automat MX-EVS (Model K4B)

This was my first Rolleiflex, purchased about three years ago. The slow shutter speeds were off so it needed stripping down and cleaning but it now works great. Rolleiflex focusing screens are notoriously dim but this camera has had a replacement fitted and the viewfinder is nice and bright.

The Carl Zeiss Tessar taking lens, although a relatively simple design, is very contrasty and incredibly sharp! Notice the new style accidental exposure prevention lock around the shutter release button (bottom left of the photo).

The MX-EVS also has the later, larger focusing knob; no need for an extension on this one! The scale on the camera body helps determine depth of field.

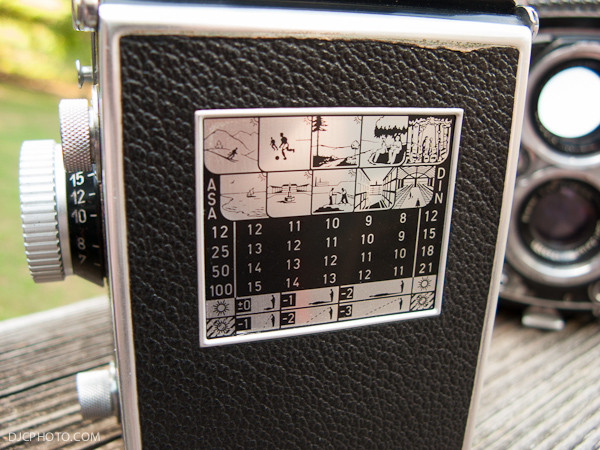

A meterless camera like the MX, the MX-EVS also has an exposure guide on the back, although the simple text explanations have given way to cryptic little diagrams.

All three of my Rolleis have the same viewing lens; the Heidosmat 75mm F/2.8.

1956 Rolleiflex 3.5 E (K4C)

My most recent find is this 1956 model E. You can read more about how I got it, and the work it needed, in this post.

This is the only of my Rolleis that has a built-in meter, although it’s currently non-functioning. It uses a selenium cell mounted above the viewing lens.

The meter display protrudes from the focusing knob, and it gives you an exposure value (EV) for the prevailing light conditions.

The EV reading from the meter can be converted to aperture and shutter speed settings using the conversion chart on the rear of the camera.

The coated 75mm F/3.5 Carl Zeiss Planar lens fitted to this camera is legendary for it’s contrast and sharpness, along with exceptional flatness of field across the entire negative area.

This camera came with the original strap with it’s hard to find ‘scissor’ connectors, but the fifty year old leather was rotted and weak. Dee took the old strap to a leather worker and had the strap replaced with new strong leather, while retaining the original mounting hardware. Good for another fifty years now!

I’ve been asked why I need three Rolleiflex cameras, and the answer is simply that I don’t! However, I’ve managed to buy all three at very good prices, and the images they produce are subtly different from each other due to the various lenses fitted, so I’m going to keep and use all of them.

I couldn’t have put it better my self. Rolleiflex is a work of art, doesn’t matter if it is a 1929 model or a 2012 model they all rock…

I concur. Rolleiflex cameras really manifest sublime beauty and advanced mechanics. I own two Rolleiflex cameras and I would never ever…ever part with them. I’d also recommend the Yashica 124 TLR, a beautiful work-horse camera that will never fail you!

I have used the cameras for over 40 years, still have a 3.5F. I photographed Princess Diana in the presidents room (Royal College of Surgeons) in Glasgow when she was pregnant for the first time- the swelling – it does show. Just the three of us in his office, I stlill have the colour negatives. The images are superb, very sharp. I was an ABIPP at the time. I still have the camera.

I have a 3.5F and a recently purchased MX Opton Tessar which I like very much. It may sound crazy but I would like to put a 45 degree prism finder on on both so that I can: (1)see an unreversed image, (2)focus faster, (3)follow the movement of 2 of the quickest kids in the world and (4)mount my 285 flash in the hot shoe (specifically if the prism is a PM 5 42308; made for a Hasselblad!!!). Could this work? You are very creative and I was just hoping to hear your thoughts.

That is not something I have attempted, but I have seen it done. For the F (or any model with interchangeable finders), there is an adapter available from Baier Fototechnik. I don’t know of any ready made solution for the MX though.

Hey there! I just bought myself a Rolleiflex and I was wondering if you could help me out a bit. How do you read the exposure chart (I have the same model as the camera you first talked about here)? It’s really only the last thing listed that I’m confused about, the ‘March, April, September’ etc. What is the 2x? I’m really used to digital photography and even then I don’t actually know what I’m doing with exposure, I just change things until it looks right.

Hi Tyler,

Congratulations on the Rolleiflex! The exposure chart is a good guideline for exposure and, in the absence of an external light meter, is perfectly adequate. TO answer your question, the guidelines given are for general conditions during the summer months (give or take), and the line at the bottom of the chart just mean that in the months mentioned, or when there is no visible sun, you have to double the exposure (the 2X).

So, taking the ‘Groups in Shadow’ at F/5.6 as an example, the chart gives a shutter speed of 1/100th second, but if you are shooting the same scene in March, you would have to double the amount of light hitting the film by exposing for twice as long: in this case, by using a shutter speed of 1/50th of a second (twice as long as 1/100th).

That’s basically it! Bear in mind that if you are shooting negative film, there is enough exposure latitude to allow for small errors in exposure, so the guidelines on this chart are really quite accurate. Shoot a roll or two and note the settings you use, and you will be become comfortable very quickly.

Good luck!

Thanks a lot! Didn’t expect a reply so soon, which is great. One other hing, do you have any film recommendations for this camera?

Because of the fairly slow maximum aperture, I tend to use Kodak Tri-X for black and white, and I used to like Fuji NPH400 for color, but I’m not sure it’s available any more. I don’t shoot a lot of color! Enjoy your Rollei!

To clarify, you said as in the example of shadows and doubling. At 2x would it not be 1/50 and then half again, 1/25th for shutter speed. Not 1/100th as mentioned. Just shooting my first roll with Asa 400 and the chart applies.

Sorry, in regards to low light, such as indoors. Longer shutter time for higher Asa film or do I still just double it based off the chart?

Hello! I just acquired my grandfathers rolleiflex. I’m so excited! I think it is the automat 1954 model K4A. How can be certain? Thanks, rebecca

Check the serial number (normally in front of the camera, at the top). This web page won’t say ‘K4A’, but maybe something like ‘automat Rolleiflex model..’.

http://www.rolleiclub.com/cameras/tlr/info/serial_numbers.shtml

I have a new-to-me K4 – either 50 or A, I will have to look at the serial number. I am so anxious to have it meld into my life.

One should not overlook the Rolleicord camera from the 1952 IV onwards. The problem with Rolleiflexes is that they were bought and used hard by professionals, perhaps putting more rolls of film through in a week than an amateur would in a year. The Rolleiflexes has a lever wind and advances the film and cocks the shutter as well. Over time, the connecting mechanism wears and the camera jams. Not a cheap repair, assuming parts are available. Now the knob-wind Rolleicord has a shutter cocking lever under the taking lens that’s also the release. What ain’t there can’t go wrong. Further, the Rolleicord was bought by amateurs who mostly kept them in tough leather cases and took very great care of them. When the IV came out, it had the 4 element Xenar lens and the Rolleiflex, that previously had this lens gained the f2.8. This is why I advised getting the IV. Overall, especially on eBay, Rolleiflexes and Rolleicords seem to be attracting similar prices. However, the Rolleiflexes often look tired, worn, neglected, but the Rolleicords seem in much smarter condition. However, I would urge anyone reading this to buy from a reputable dealer who has thoroughly tested the camera and offers a warranty. My Rolleicord IV came in a beautiful leather case with hood and cable release also in a leather case, from Ffordes of Inverness (Scotland) for £79 + carriage with 6 months warranty.